By Zag industry expert Lars Christian Grødem-Olsen, an Advisor for Movability on new mobility and former Country Manager at Tier.

Damian Bown has spent the past 20 years building apps and sites that make it easier to travel around cities.

With Kizoom he built the world’s first public transport journey planner on a phone in 2000. Then, after a brief stint running his own bus company, he led Citymapper’s Business Development team, before joining Trafi in 2020 as CEO.

Founded in 2013, Trafi is a Lithuanian mobility-as-a-service (MaaS) platform that lets users plan, book and pay for various modes of transportation within a city. It already boasts Google, BVG (Berlin) and STIB-MIVB (Brussels) as customers.

Zag Daily: Let’s start with the basics. Many believe that Mobility as a Service, or MaaS, is a function that helps people tap into the network of transportation options available from a single application. Is that right?

Damian: “I don’t think MaaS is an app. MaaS is whatever the societal infrastructure provides so that grabbing your car keys is not the only option. It’s about tackling the availability of services and the accessibility of information. How do you know what there is to use, the cost, and schedule? An app can inform, but it can’t create availability.”

Zag: Can you provide an example?

Damian: “In areas with simple transit, a MaaS app is useless if your only bus comes every three hours. It’s more services that are needed. Take London, where I live with my family, there’s a wealth of transport options. I’ve got very good tube lines, train lines, bus services, bikes, scooter availability, and most importantly, car rental on demand.

“For the 95% of my journeys that I’m happy to do by public transport, that’s available, and the 5% where I do need a car – because I’m carrying something, or I’m going to a place that I can’t get by public transport – I’ve got an easily available option. That combination is how I’ve lived without a car now for five years with a family of two kids, and I wouldn’t go back.

“Each of those things in London have separate apps and separate accounts. MaaS to me is about enabling that wealth of choice, rather than just being a digital interface for it.”

Zag: Am I right to say that you are describing a Tier One mobility area like London, versus a Tier Three, urban sprawl? How would you help people in those more rural areas live without a car?

Damian: “I believe in launching services where they’re most likely to thrive and creating a domino effect. Pinpoint areas in a city with abundant services and encourage the locals to try new ways of living, like offering incentives for going car-free. This attracts not just residents but also early adopters from outside the region. The demand generated can then prompt service providers to expand their region of coverage. You begin with a strong, localised success story, which acts like a marine reserve, a protected area that supports a robust ecosystem. Fish don’t recognise boundaries and will spread out, similar to how successful service areas can organically grow, pushing the perimeter of service availability further.”

Zag: There was a theory that a private MaaS app could be profitable for the MaaS app provider. Instead of paying for a bus and a train pass, you’re just paying a single subscription. Can you tell me what happened when you tested that model?

Damian: “I built my first mobile journey planner back in 1999 – six years before the iPhone. People needed travel information on the go. With WAP technology from Nokia, it just clicked. We started with static journey planning, then we added live incidents, then real-time data. Citymapper and others made the interfaces super intuitive and map-based. The whole industry, including Google, followed that path.

“The term MaaS popped up about five or six years ago, promising to revolutionise travel by getting people out of their cars through an app that bundled different transport modes. Adding scooter and bike options to journey planners didn’t seem revolutionary to me, it was more like the next logical step in the evolution of the service I’ve been improving over decades.

“As MaaS was gaining traction, I noticed cities were moving away from travel passes to a more flexible, contactless, pay-as-you-go system for payment. The best systems capped your spending when you hit a certain amount, so there’s no need to commit to a bundle upfront. It’s the opposite of bundling, really.

“This threw me because it showed a clear disconnect between the MaaS promise and the public’s actual behaviour. People had the choice between the all-you-can-eat Oyster pass or the tap-and-go contactless option in London. And the data was clear—they preferred the flexibility and simplicity of the contactless option. This choice has consistently outperformed bundled passes, suggesting that users value the convenience and flexibility of pay-as-you-go over the predicted savings of bundling.”

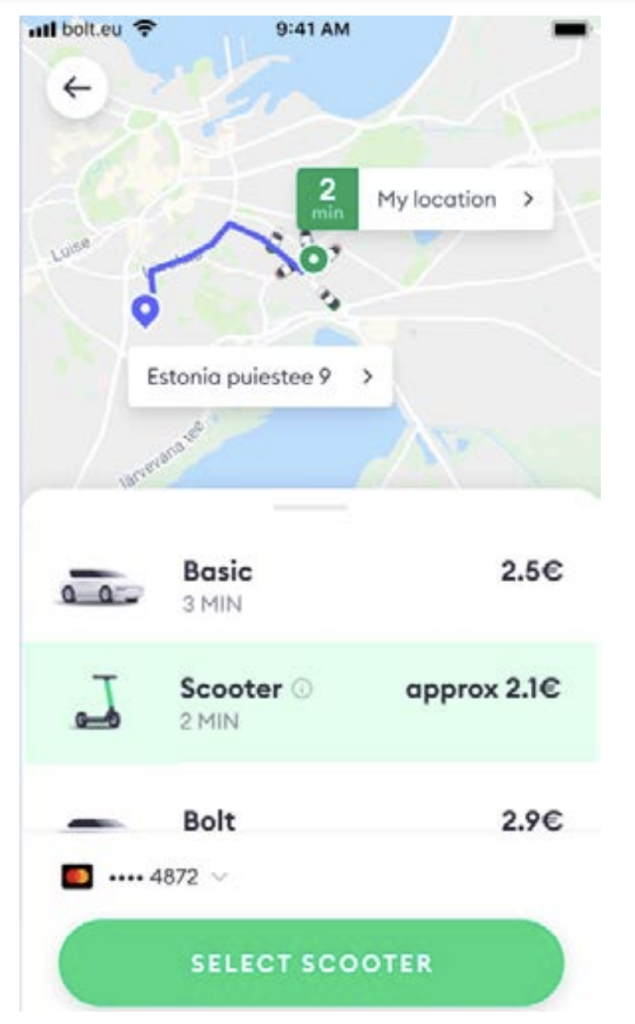

| Text box: Bolt introduced a “nudging” feature in its app to encourage users to switch from ride-hailing to e-scooters in several European cities. The experiment aimed to ‘nudge’ users by offering e-scooter information more prominently in the ride-hailing section of the app, given specific criteria. Nudging was effective: e-scooter shares among nudged users increased by 40-200%, and in Oslo, 55% of the e-scooter trips caused by the nudge replaced ride hail trips. The results emphasise that altering in-app information can efficiently switch users from cars without any additional cost to the user. |

Zag: This idea of preference is interesting, which brings me to a study the Norwegian Institute of Transport Economics Institute ran in several places in Europe. Essentially, when Bolt put micromobility at the top of trip alternatives, it found an immense uptick in that option for shorter trips. Have you seen any data on similar phenomena?

Damian: “The science is actually quite split. However, in a study I conducted where we randomised journey results, it was clear the order heavily influences people’s choices. We had hoped to refine our planner using user preferences. If a bus was consistently chosen over a train or scooter, it meant we should prioritise it. All we learned was that people tend to select the first option presented, regardless of the order—50% chose the first, 33% the second, 10% the third, and so on. Randomisation told us that positioning, not preference, drove their choices.”

Zag: Pivoting a bit to apps and the infrastructure for MaaS. Why do some Public Transport Authorities try building apps while others are more willing to buy?

Damian: “The ‘build or buy’ debate leans towards using what’s already successful and spreading that fixed cost across a wider geographic area to make the business case work. If you’re going to compete with the likes of Google and Citymapper for user eyeballs, you have to keep up with this sort of brutal arms race of features and improvements and upgrades both to devices and the way people expect to see their apps look. Trying to do it on a standalone city-by-city basis is a really tough call. It’s why at Trafi we have leveraged the same platform to build Berlin’s Jelbi; the UK’s Breeze, Basel, and Bern; Zurich’s Yumuv; and Munich’s MVGo.

“With few city-scale providers for ticketing, payments, ID validation, or micromobility, and their numbers dwindling, many share costly tech backends. This presents an opportunity to leverage existing integrations. If, when assessing a new city’s tech like PSBs or ticketing systems, most are pre-integrated, it significantly reduces the cost of trial implementation.”

Zag Daily: So then why do some PTAs choose to build?

Damian: “The main reason PTAs consider building in-house is the perceived need for creative control and flexibility in user interface and features. They often believe they must own the entire technology stack to achieve this. However, that’s more relevant if you’re talking about developing an app, not the entire platform.

“With Trafi, our core product is not the app the users interact with, but the sophisticated integration system behind it. Clients can build their apps on top of our platform. MaaS in its current form is essentially offloading the cognitive load of integration from the user to the platform. Our clients have the freedom to innovate on the front end while leveraging Trafi’s backend. For example, a city could integrate local tourist sites or theater bookings into their version of the app to add unique value, whilst taking advantage of the existing MSP integrations and billing logic in the Trafi MaaS Platform beneath the app.”

Zag: Do you see any hesitancy about working with a startup? I understand Trafi started in 2013, and did its Series-B round in 2020. Capital markets have been brutal lately and we are seeing more investors demanding profitability.

Damian: “Trafi reached profitability as of 2023, unlike pretty much anyone else in our sector. Another concern PTAs have is the longevity and reliability of working with a startup. If you’re a city planner playing the long game with your infrastructure, you’ve got to weigh the risks. This isn’t just about MaaS. What if the company you rely on gets snapped up or tanks?

“I can see the draw of cities wanting to build their tech stack ground-up for that ironclad security, even if it means tech advancements come at a snail’s pace. It’s a trade-off. What I find challenging is when urban IT departments become enamored with the idea of app development as though it’s a novel concept. Expecting in-house teams to surpass Google Maps is ambitious. At Trafi, we’ve dedicated over a decade to perfecting city MaaS apps. We offer a unique perspective that even Google lacks—comprehensive insights and control over urban transportation, including disruptions.”

Zag: One of the primary challenges with any MaaS app, including Google Maps, is navigating the complexity of the many choices available to users. How does Trafi manage this?

Damian: “When we converse with our clients, a frequent topic is customization options, which presents a dilemma. They want to shift user behaviour towards more sustainable modes of transport. But at the same time they want to let users customise the app to only recommend familiar modes. The ideal approach is to subtly present users with the best immediate option, while also highlighting potential alternatives that might be cheaper, faster, or more environmentally friendly.”

Zag: Where do you envision this development? How do you continue to shift that user behaviour in the right direction?

Damian: “Looking ahead, I envision road pricing becoming a standard. Users will be faced with choices: pay a premium for using road space or opt for cheaper public transport options. This decision-making process should be integrated, establishing the app as an essential tool for cities to manage and optimise their transport networks. In this way a trip with a ride-hailing service is more expensive than a trip with a tram for the same route.”

Fig: Olaf Sakker’s framework Trip economy posits that we’ve seen the private car unbundled to different kinds of trips, such as ride-hailing or micromobility.

Fig: The Trip economy framework envisions that regulators are enabled to regulate the cost of externalities into the trip price.

Zag Daily: There is also this idea now of seamless roaming where travellers move from one city to another using the same app to get tickets in, say, Berlin and Munich. Is this something Trafi is working on?

Damian: “It’s a fascinating challenge, one that’s ripe for innovation. Ideally, Trafi would enable users to carry their city preferences from Berlin, Brussels, or any other big city we cover, right into a new city without skipping a beat. The reality is that it’s a technical minefield, riddled with data ownership and privacy laws like GDPR. Either our technology has to evolve to handle it, or there’s a regulatory shift towards making user data universally portable. Then there is the question of who takes accountability when a traveller faces issues?

“Despite these hurdles, I do see a trend towards a roaming profile concept. Should our app morph to handle multiple cities, or will there be an intuitive nudge towards a local app when you land in a new place? It’s still up in the air.”

Zag Daily: Sounds like the nudge towards a local app might be the easier path for now. It would just be a matter of syncing up with the local terms and user interface.

Damian: “There are always a few forward-thinking cities that lead such shifts. Perhaps a partnership between them could offer a blueprint for others. If city pairs start collaborating, that could be a catalyst for innovation. It’s a difficult problem and one that needs to be solved. It frequently comes up in tenders. There is widespread industry awareness and a desire to address it. Yet, nobody has pinpointed an approach, whether through legislation or innovation, that effectively tackles the challenge.”