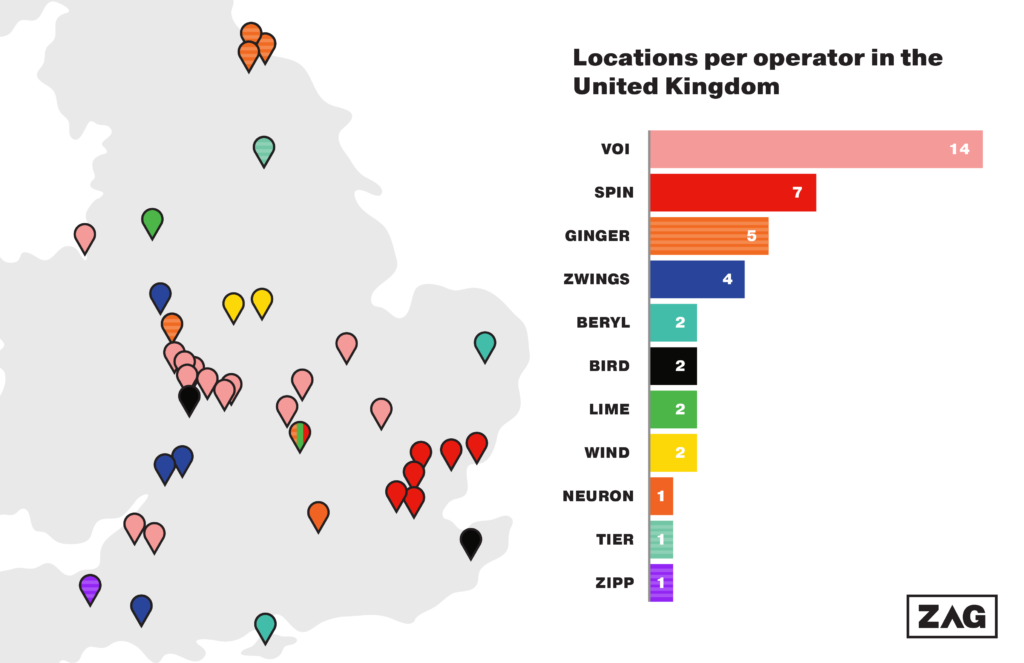

England’s electric scooter trial locations are almost all sewn up now, with just a few remaining. Here’s a handy chart that shows which micromobility operators have won which locations, as of today.

The winners and losers are surprising. Tiny start-ups Ginger and Zwings have won more locations than industry stalwarts Bird, Lime and Neuron – and we believe there are more to come from both. And Swedish firm Voi has swept the board, with twice as many locations as its nearest rival and, once all its trials come on-stream, more e-scooters on British streets than all other operators put together.

There are some caveats. The six cities in Essex, for example, are part of the same trial. Remove those and Spin suddenly looks as vulnerable as Bird and Lime. The same is true, to a lesser extent, of Ginger, where the cluster of three north-easterly towns are also all under the same umbrella. And Voi’s expansive West Midlands programme spans seven locations.

(Talking of which, we expect to see Coventry back in action very soon.)

The overwhelming impression, however, is the opposite of that seen in more mature micromobility markets around the world, where established and experienced players such as Bird, Lime and Spin dominate and tiny players of the Zwings, Ginger and Zipp ilk simply can’t compete.

So what’s happened? There are a few factors to consider. Firstly, fleet operators are private businesses. Whether they’re bidding to win a trial or a permanent location, they need to make profit. The small scale of many trials, combined with the inherent uncertainty of a trial transitioning into a long-term contract, made them unattractive propositions to even bid for, for many bigger companies. That’s one reason why there’s another glaring omission from this chart: Dott, one of the three e-scooter providers looking after Paris. It’s a lack of appetite on the side of the operators, not the cities.

Secondly, that small scale has lowered the barriers to entry for start-up businesses. Investing in 100 e-scooters is far more attainable than the 10,000 Voi has promised in the West Midlands alone; many pilot programmes have called for tens of scooters, not hundreds. The trademark ferocious agility that start-ups often posses (and often lose as scale-ups) is perfectly suited to securing investors and contracts in a very short space of time. Many councils running programmes of a limited size like the fact that they can pick up the phone and talk directly to Joe (Zwings boss) or Paul (Ginger chief); there are no layers of hierarchy to work through and there’s little staff churn yet.

Thirdly, these trials were originally intended to be run next year. When the DfT suddenly fast-tracked the pilots, many operators (most of whom are based abroad) were left to scramble British teams at the height of lockdown. Not an easy task. The situation advantaged British companies, such as Ginger and Zwings, and British staff who had already been working in similar fields here, such as Richard Corbett (formerly Bird, now Voi) and Steve Pyer (who, prior to running country operations for Spin, worked on London’s bike-share scheme with Serco).

There are some major drawbacks to using a start-up in this space rather than an established business and they can be summed up thus: experience, technology, logistics. The bigger companies have been at it a while. They know how to introduce e-scooters to cities smoothly, because they’ve made all the early mistakes. They have iterated and iterated and iterated, and many now have custom-designed scooters and powerful software.

And they have the funds to invest in enough operational staff to keep abreast of repairs, bad parking, education and community engagement (Voi, for example, has reportedly signed up to tens of millions of pounds in investment to finance its UK locations). Micro-businesses have none of these things, and that’s a risk for trial cities and the future of e-scooters in the entire country.

What will the situation look like next year? Much of that depends on what the DfT decides to do and how local authorities view the operators. If shared e-scooters are legalised, then it becomes a question of market forces versus public funding. Programmes with very limited numbers of scooters and operating areas are unlikely to be financially viable in the long-term and risk simply fading away without support. Even large operations, such as Voi’s, need to make profit without betting the farm.

If councils see value in them, there may be a conversation to be had around subsidies. Why? Because scooters are low-carbon transport solutions and British cities badly need to clean up their act, and the level of investment is nowhere near that required by buses, trams or trains.

There’s also the question of operating licence fees. In other countries, operators must pay local authorities in order to operate in that location. For British trials, that isn’t the case. We’d argue that neither should this be the case in the long-term, if cities and government really are serious about reducing our carbon footprint by tackling the volume of motor vehicles.

Could smaller micromobility entities be bought out by the larger companies, mirroring the consolidation seen in more mature markets? Possibly, but unlikely. If there’s no realistic prospect of pulling in big numbers, the bottom line will speak loudest and the big providers will stick to the big areas. Councils, of course, could get clever and introduce clauses whereby fleet providers have to provide scooters in smaller areas as a condition of operating in the more populated, more lucrative areas.

Shared e-scooters offer Britain a real opportunity to redress the balance when it comes to giving all communities across the country equitable access to transport solutions. Their combination of on-street hire and long-term personal leases puts e-scooters in a brand new bracket, spanning the appeal of personal mobility (cars) with the affordability and carbon-cutting benefits of public transport.

The next 12 months will be fascinating. We just hope that among the legal wrangling, lurid headlines, profit margins and bright, bright branding colours, the British public and the communities who most need low-cost, accessible transport do not get forgotten.

–

This article was updated on 23 October 2020 to reflect the accurate number of locations won by Voi.