Lola Bushnell, Senior Sustainable Futures Strategist and lead author of Designing for planetary boundary cities, Arup

Humans are part of nature, yet we are most unusual in the natural world. If you were to put Earth’s history on a calendar year, humans would have arrived late on the 31st of December, and in the last seconds of it, become the most influential species in the history of the planet with an abnormal ability to irreversibly alter our planetary systems.

The Earth as we know it today – from its temperature and weather patterns to the distribution of species that pollinate our crops – has been billions of years in the making through the gradual evolution of our Earth systems. Human behaviour is accelerating the change that is now threatening this balance: we are experiencing the impacts of climate change and ecological damage all around us as we rapidly approach our planet’s biophysical tipping elements.

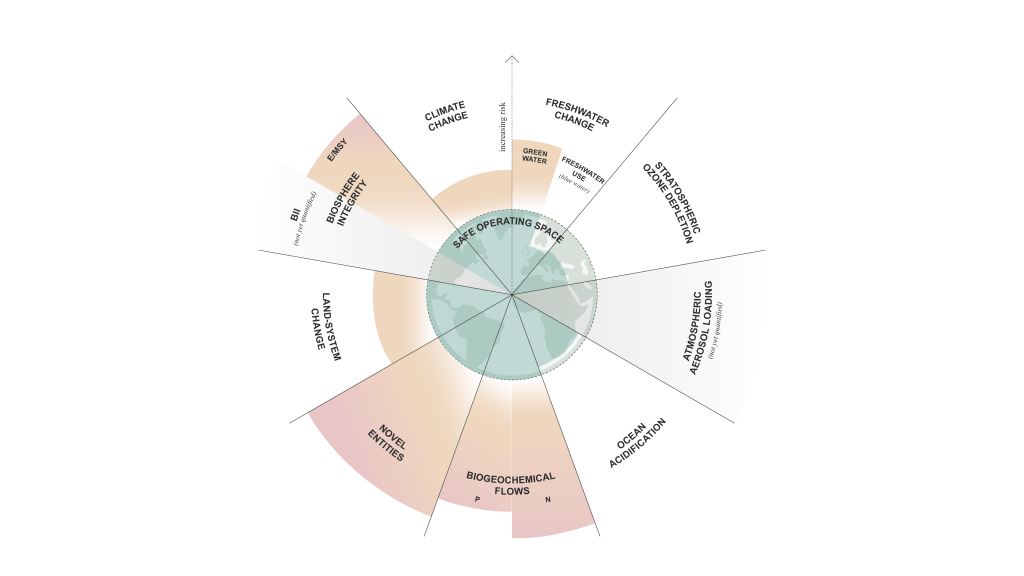

In 2009, the Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC) created the Planetary Boundaries Framework, defining the limits of acceptable change within nine of Earth’s key system processes. Simply put, these offer the guardrails for containing and reducing ecological harm, outlining thresholds for irreversible harm to our planet and its interconnected systems. We have already crossed five of the nine – indicating that we may be on the verge of pushing our entire Earth system to a state not seen in the past three million years, long before humans walked the earth.

Despite these grave prospects, we now have the knowledge and technical capability to inform progress. We are the first generation with sufficient data and computing power to understand and articulate what is happening to our planet because of our collective behaviour. Because of this, we have the unique opportunity and responsibility to action change – most notably by transitioning our impact from degenerative to regenerative.

To mobilise this change, we must evolve the way we think about our built environment and design our cities accordingly. As an important mechanism for decarbonisation, regenerative design prioritises nature and begins to mitigate further harm to our planetary resources. There is an ever-growing spectrum of regenerative actions available to city designers and planners, ranging from nature-based wastewater solutions to design interventions for public and active mobility. Although varied, these measures are entirely interconnected and embrace a new philosophy that engages the natural world as a co-creator during design stages, enabling regeneration and restoration.

This can be broken into two measures:

- Designing for nature by giving it space to flourish. This means reducing extractive + polluting pressures via strong circular economies that work in harmony with the cycles of nature. At design stages, we can reduce the amount of composite and toxic materials so that resources can be easily reused and reintegrated into natural systems. This brings nature in as a key stakeholder, considered in all decisions.

- Designing with nature by enabling it to do what it was evolved to do. This means letting biodiversity thrive and perform the functions that we seek to re-engineer, such as decomposition, filtration and storage of water. Nature is effectively a catalogue of products that has benefitted from 3.8bn years of natural research and development through evolutionary selection.

In Arup’s recent report Designing for Planetary Boundary Cities, we look at how cities can design for clean and efficient public transportation systems and active travel infrastructure to support our natural ecosystems. As integrated regenerative actions, these elements further the pathway to net zero. Well-designed public transit systems can reduce aerosols emitted from combustion engines and reduce CO2 to alleviate consequential planetary impacts such as ocean acidification. The report explores Amsterdam’s Smart City Programme as an example of collaboration and innovation to solve mobility problems, such as congestion and crowding, in a metropolis.

Our urban environments play a key role in shaping humanity’s relationship with the wider natural world.

Through sustainable design, we are making important progress in beginning to mitigate further damage to our natural systems, but we must go further. Restorative design aims to repair prior damage, yet the fundamental aim of regenerative design is to leverage humans’ unique position on Earth and better participate in the wider natural system.

This Autumn, Arup will release new research exploring regenerative design, extending our understanding of planetary boundaries in the context of the built environment.