Author: Isobel Duxfield, Fundraising Manager at Our Community Bikes (OCB), a Vancouver based non-profit dedicated to promoting cycling, education and sustainability. Isobel previously worked at POLIS Network where she helped develop the World Bank’s Gender Equality in the Transport Sector Guidelines

Image Credit: OCB

Bike share should have been the biggest transformation in inclusive urban transport to date – except it wasn’t.

Analyses of schemes over the last decade exhibit that users are disproportionately young, male, white, highly educated, and from higher income groups. Women in North America and Europe make up only a quarter of users, while individuals from low-income backgrounds and people of colour are also far less likely to use bike share services.

These are disappointing stats (putting it mildly), especially given the clear potential for sharing programs to expand mobility options for those with barriers to owning a bike.

“Building equitable access to mobility is essential, as shared mobility evolves, we need to be able to serve everyone,” says Dagmara Wrzesinska, Mobility Expert and Intermobility Board Member.

Despite equity initiatives like community passes from public providers like Vancouver’s Mobi and BikeTOWN in Portland (USA), emergence of innovative ventures such as A Fleet for Change, UpGirl and Matterz, as well as industry action like Intermobility and The Better Bike Share Partnership, access and inclusion programs have failed to significantly change ridership demographics.

“Most cities focus on bridging the income disparity in ridership stats and operators are mandated to deploy services in neighbourhoods with a low average median income, yet in many cases other axes of diversity are left out,” asserts Venkatesh Gopal, CEO of Movmi, a Canadian agency specialising in design, planning and launch of new shared mobility services.

This is hurting shared mobility’s bottom line too.

“Ridership growth depends on improving diversity; there’s a big opportunity in tapping into female riders, a wider income and age bracket. More ridership means better economics for operators which has been a persistent challenge for many globally,” Gopal points out.

Change starts in the community

Instead, it has been community bike shops which have been transforming access to cycling for low-income communities, people of colour and less represented gender identities.

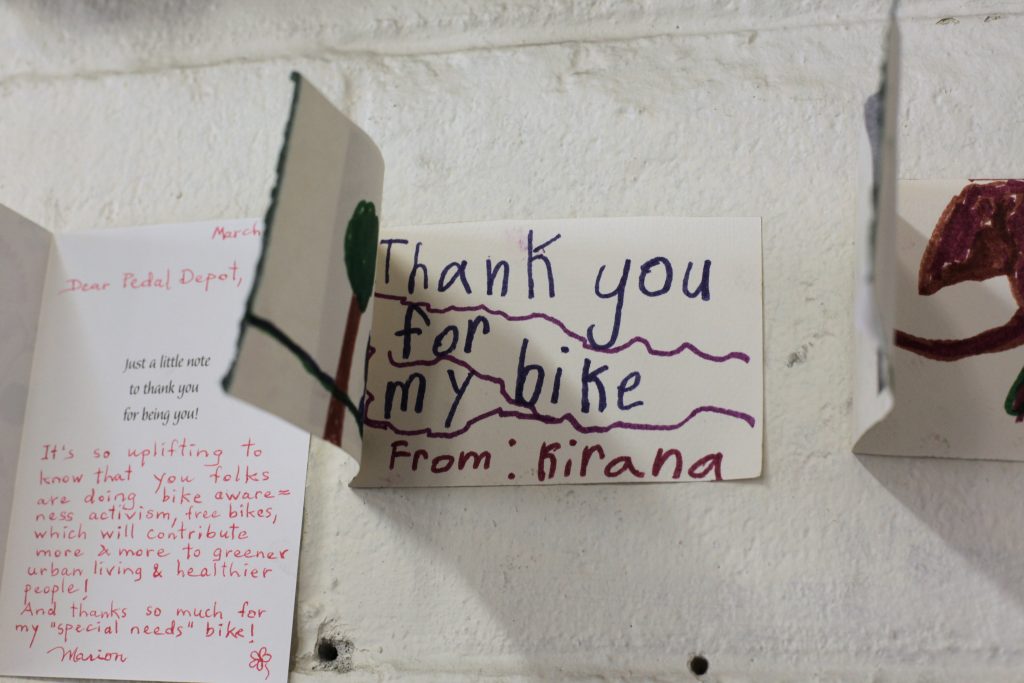

For anybody who has not frequented a community bike shop, these are not your traditional cycle retail outlet. Offering low-cost and free mechanics workshops, traffic navigation training, free repairs, as well as donations of bikes, parts and accessories, these spaces (found in cities around the world) have engaged low-income and diverse communities in cycling for decades.

“In North America, cycling may be becoming less marginalised, but it is far from normalised for many communities,” says Cavan Hua, floor lead at Our Community Bikes, open in Vancouver since 1993.

Our Community Bikes (OCB) is not alone. From Bikes for Humanity, the Bike Church and Bike Kitchen along America’s west coast, as well as the Bike Foundry and Broken Spoke in the UK, community bike shops cater to individuals who have found themselves at the margins of urban transit.

Their secret to success? Every metropolis has unique cultures and geographies which – as countless bike share operations have discovered, often to their detriment – shape engagement with pedal power. Community bike shops have placed roots firmly in the local cycling scene; they know what works… and what doesn’t.

Community bike shops: the secret to transformational change?

At first glance, community bike shops and bike share appear to be adversaries; the first helping folks own and maintain their own bicycles, the latter providing cooperative wheels. However, they are in fact on the same side of the battle to bring cycling to the masses.

As a result, working with community bike shops is a unique entry point for the cycle share sector to engage more comprehensively with diversity and inclusion in a targeted and durable way.

“Collaboration between the shared mobility sector and local communities will ensure that meaningful, community-led input remains central to innovation,”asserts Wrzesinska.

For example, partnering on access programs is a direct means of promoting active bicycling cultures amongst a new generation of riders. For example, OCB, delivers regular DIY Access Nights endeavouring to attract new folks to cycling, including Youth Clubs, Women/Trans/Queer nights, and Deaf/HoH [Hard of Hearing] events.

This has ripple effects across the entire community, with those engaging in the programs inspiring their families and wider peer networks to see cycling as a means of transit “for them”– something bike share has, thus far, roundly failed to achieve.

Assisting community Bike Shops’ free maintenance services and distribution of essential riding gear could also shift cycle share ridership.

For example, last year alone, OCB’s Oppenheimer Clinic provided 1,400 free repairs and distributed 400 locks, lights and helmets across Vancouver, yet limited resources places these services under threat. Supporting such initiatives, bike share can not just boost cycling, but also gain a direct insight into the everyday challenges facing local communities.

“Each time we make a new voice heard, we get closer to ensuring the next era of mobility will account for all those unheard by today’s ecosystems,” Wrzesinska reflects.

Reshaping the face of the sector

Community bike shops also offer an avenue for accessing new and diverse talent, reshaping the face of the sector itself.

Behind cycle share’s failure to reach marginalized populations is its struggle to address its own diversity problem. Market voices in North America and Europe from North American Bikeshare Association(NABSA), to InterMobility and Movmi have been placing growing emphasis on the urgency for change. We have seen the emergence of a scattering of inclusive employment initiatives; however, numbers are not changing fast enough, and despite many platitudes at recent industry events, action on the ground has been lethargic.

In contrast, community bike shops have been directly supporting new and diverse talent. For example, OCB’s Gear Up program is a free 13-week course (delivered year round) that equips youth ages 15 – 30 with the skills, certification and employer connections necessary to work as a bike mechanic.

“Cycling is very white, cis-male dominated, and as a result we frequently see toxic working cultures develop. With these programmes, and also through the collaborative and deliberative way we work at OCB ourselves, we are trying to change this,” says Hua.

Over in the UK, The Bike Foundry coordinates similar projects, working with local colleges to offer fully funded courses.

Cooperating with community bike shops to sponsor new recruits through such training programs, or offering job-search support to students is a direct – and not to mention financially advantageous – avenue for bike share to reach skilled personnel, nurturing individuals who would not otherwise have the opportunity to enter the industry.

A shared future

Whichever strategies it adopts, the bike share industry will need to put its money where its mouth is to diversify its ridership and the sector itself. Failure to do so risks the posterity of operations, and indeed the legitimacy of cycle sharing as a sustainable and just solution to urban car-centricity.

However, simply chucking cash at the problem is not a viable solution, not that many have the capital to do so right now anyway.

“Equity programs in cities such as Vancouver, Montreal, Washington and New York work well and have seen some promising impact; yet the challenge remains that the equity programs put pressure on the bottom line for operators,” says Gopal.

As such, working with Community Bike Shops offers a direct pathway into the heart of the local cycling motivations and barriers, securing effective and enduring inclusion and diversity agendas.